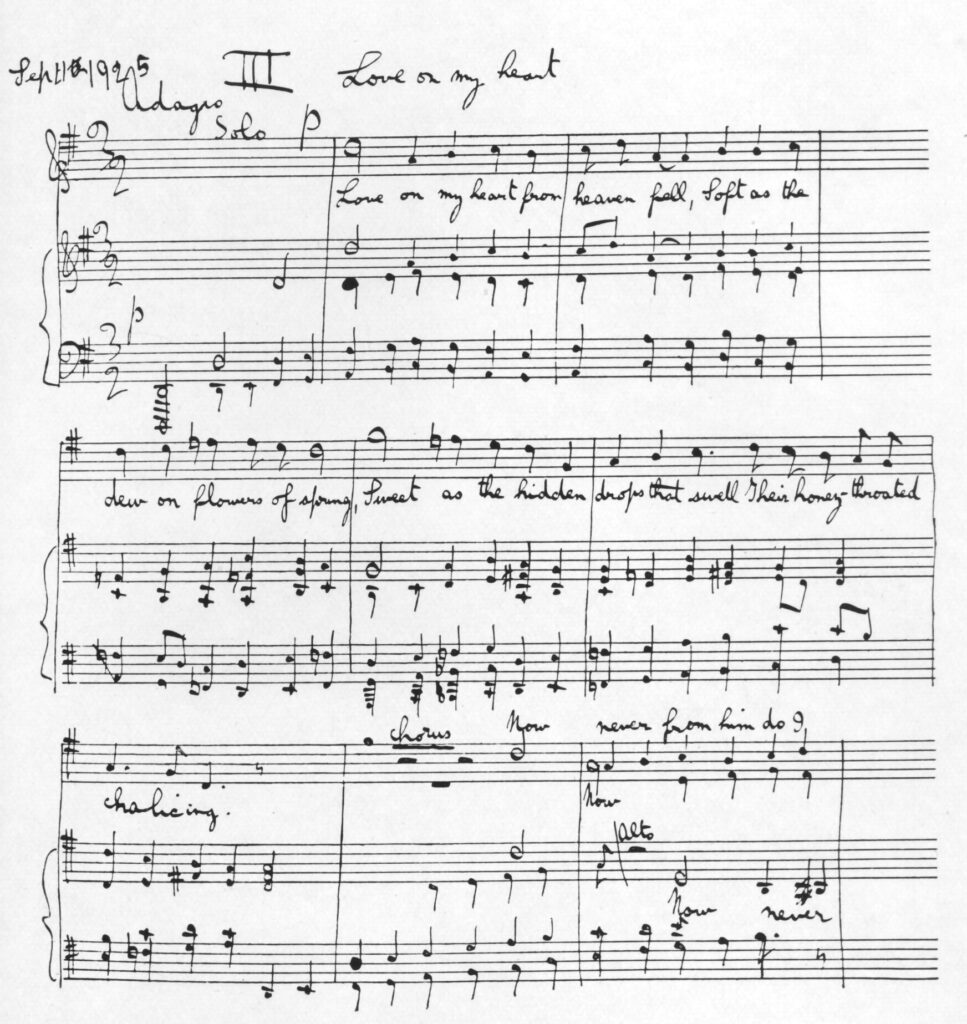

After spending several months on a holiday in Italy, Gustav Holst returned to England feeling refreshed. As Michael Short notes, he came back “eager to compose” and, for the first time in over twenty years, felt the urge to write for solo voice and piano, a medium he had not seriously touched since his Vedic Hymns of 1907.

The catalyst for this sudden creative burst was the poetry of Humbert Wolfe. Holst selected thirteen poems that resonated with his own eclectic nature. The resulting collection serves as a bridge between the icy intellectualism of his mid-1920s works and the lyrical warmth of his final period. In songs like The Dream-City, Holst evokes the London he considered “the most adorable city in the world,” capturing the atmosphere of Kensington and Kew. Conversely, Betelgeuse allowed him to revisit the cold, mystical territory of Neptune. Imogen Holst describes this song as a “terrifying vision of the vastness of space,” achieved through “skeletal chords” and juxtapositions of perfect fifths that create a static, frozen atmosphere.

It is remarkable that Holst, who was not a pianist and whose neuritis often prevented him from playing, produced accompaniments of such fluidity in this set. After the accusations of lack of virtuosity in pieces like the Double Concerto for two violins, Imogen Holst observed that the writing shows a “sensuous delight in being pianistic” that he had rarely allowed himself before. In songs such as Things Lovelier and The Thought, he dispensed with time signatures entirely, allowing the music to flow solely according to the speech-rhythm of the poetry.

The songs received their first performance not in a concert hall, but at a private gathering in Paris on Saturday, November 9, 1929. The event was hosted by Louise Dyer, the Australian patron and founder of Lyre-Bird Press, at her apartment. Holst traveled to Paris specifically for the occasion, accompanied by the soprano Dorothy Silk and his loyal amanuensis Vally Lasker, who played the piano accompaniment. During this trip to Paris, Holst also met with Nadia Boulanger and her mother, but it is not known if she attended the premiere of this set.

The first public performance followed at Wigmore Hall in February 1930. While the critics praised the “spare” and “bleak” style, perhaps the most significant reaction came from the composer himself. Ian Lace recounts a pivotal moment following the concert. The program ended with the Schubert Quintet in C Major. As Holst listened to the radiant warmth of Schubert’s music immediately after his own austere songs, he was struck by a sense of despair. He realized he had “clung to his austerity” too tightly and missed the human warmth that Schubert possessed. This revelation sparked a desire to reclaim that warmth in his final works, such as the Lyric Movement.

Holst did not intend these songs to form a rigid song cycle. He explicitly stated that singers were at liberty to select as many as they wished and to change the order. However, history has largely solidified the twelve-song set we know today, an order established by the tenor Peter Pears and confirmed by Imogen Holst’s thematic catalogue (H. 174).

As I mentioned earlier, Holst originally set thirteen poems. He discarded one titled Epilogue, leaving the twelve standard songs. While Epilogue remained unpublished for decades, it has since been recorded and released, offering modern listeners a complete view of Holst’s initial vision for this collection.

Bibliography

- Dickinson, A.E.F. Holst’s Music: A Guide. London: Thames Publishing, 1995.

- Holst, Imogen. The Music of Gustav Holst and Holst’s Music Reconsidered. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Lace, Ian. “A Biography of Gustav Holst.” The Gustav Holst Website, 1995

- Mitchell, Jon C. A Comprehensive Biography of Composer Gustav Holst with Correspondence and Diary Excerpts.Lewiston, N.Y.: E. Mellen Press, 2001.

- Short, Michael. Gustav Holst: The Man and His Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.