To many listeners, Gustav Holst is simply the man who wrote The Planets. It is a label that stuck to him during his lifetime and, frustratingly, persists today. Yet, for those of us who have dug a little deeper into his catalogue, the real joy often lies in the “hidden” Holst: the works where he stripped away the massive orchestration of Mars and found a voice of absolute clarity and economy.

Nowhere is this more evident than in his final opera, The Wandering Scholar, Op. 50.

I have always felt it is a tragedy that Holst never heard this work performed. Composed between 1929 and 1930, during a period of declining health, it kind od represents the end of a long, often difficult journey for the composer. If we look back at his operatic career, it is a road paved with inconsistency, but full of gems. We have the “good old Wagnerian bawling” of his youth in Sita, the mystical minimalism of Savitri, and the clever but rhythmically strait-jacketed At the Boar’s Head.

But in The Wandering Scholar, I feel like Holst finally cracked the code. He abandoned the safety net of borrowed folk tunes and wrote his own melodies. These tunes sound authentically English yet allowed him the freedom to manipulate the rhythm to match the quick-fire comedy of the libretto. The pacing of the drama has always felt a bit like episodic television to me, feeling much more modern than something from the 1920s, and reminiscent of an “I Love Lucy” bit.

The genesis of the opera is delightful in itself. Holst had been reading Helen Waddell’s book The Wandering Scholars and found it captivating. He enlisted his friend Clifford Bax to fashion a libretto from one of its tales. One can imagine the scene with the two friends meeting up at Hammersmith, discussing the flow of the drama over glasses of burgundy.

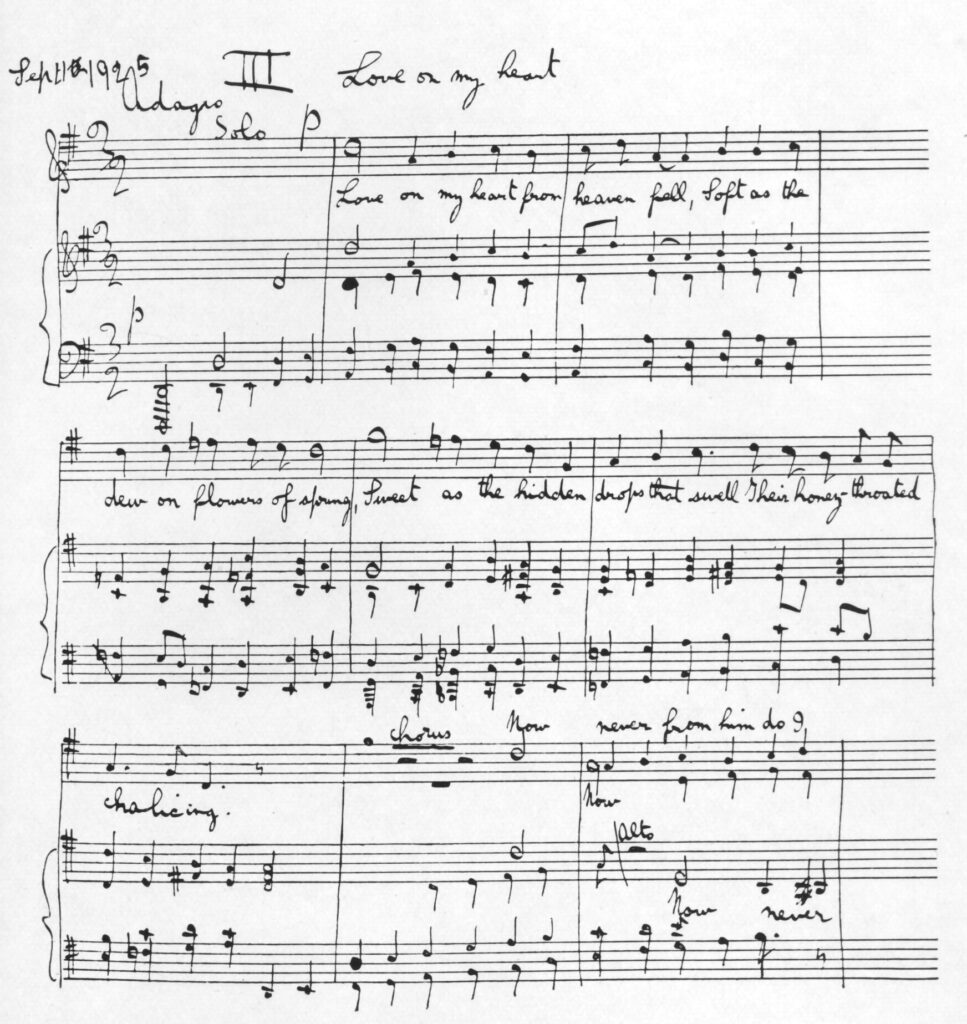

Sadly, the actual writing was a physical struggle. Plagued by neuritis in his arm, Holst had to rely on his dedicated “scribes”, Vally Lasker and Nora Day, to help commit the score to paper.

The plot is a humorous farce set in a 13th-century French farm kitchen. It is a simple enough triangle (or quadrangle): Louis, the farmer; Alison, his “comely” wife; Father Philippe, a lusty priest with more than just spiritual comfort on his mind; and Pierre, the starving scholar who interrupts their tryst.

What strikes me most about this score is its sheer speed. There is no overture to settle the audience. There are just a few bars of introduction and we are off. The vocal lines are conversational, shifting rapidly between speech-rhythm and lyricism. Musical ideas that other composers might have milked for five minutes are stated by Holst in five seconds and then discarded. It is music stripped to the bone.

The harmonic language is mature Holst at his best. Note the opening “side-slipped” fourths that move in and out of G major. It creates a sound world that is at once modern yet entirely accessible, light years away from the heavy romanticism of his youth.

Legacy

The opera premiered in Liverpool in January 1934, but Holst was too ill to attend. He died that May, leaving the score with pencilled queries like “Tempo?” and “More harmony?” These were questions that would eventually be answered by his daughter Imogen and Benjamin Britten when they prepared the work for publication years later.

For me, The Wandering Scholar is the perfect chamber opera. It is fleet, humorous, and devoid of a single wasted note. It proves that at the very end of his life, Holst had achieved the artistic freedom to be “unbuttoned” and human while maintaining the most rigorous standards of craftsmanship. It makes me wish of what could have been in his later period of composition, as I find many of these pieces from this time so forward thinking.

Bibliography

Short, Michael. Gustav Holst: The Man and His Music. Oxford University Press, 1990.

Dickinson, A.E.F. Holst’s Music: A Guide. London: Thames Publishing, 1995.

Holst, Imogen. The Music of Gustav Holst. Oxford University Press, 1986.