If The Planets represented an outward gaze toward the cosmos, the First Choral Symphony was the product of an inward retreat. By 1923, Holst was paying the physical price for his sudden celebrity. Following a concussion sustained from a fall on a podium and battling nervous exhaustion, he was ordered by doctors to take a break from all of his professional duties. Holst withdrew from his teaching posts to seek recovery in Thaxted. There, cared for by an ex-army batman who managed his domestic needs, he settled into what he described as a “humdrum and monotonous existence.”

It was within this deliberate quiet, far removed from the London limelight, that Holst crafted what he believed to be his masterpiece. He wrote to his friend W.G. Whittaker that “the work as a whole is the best thing I have written,” and titled it the First Choral Symphony in the anticipation of a successor that would ultimately exist only in fragments.

“The Keats Symphony”

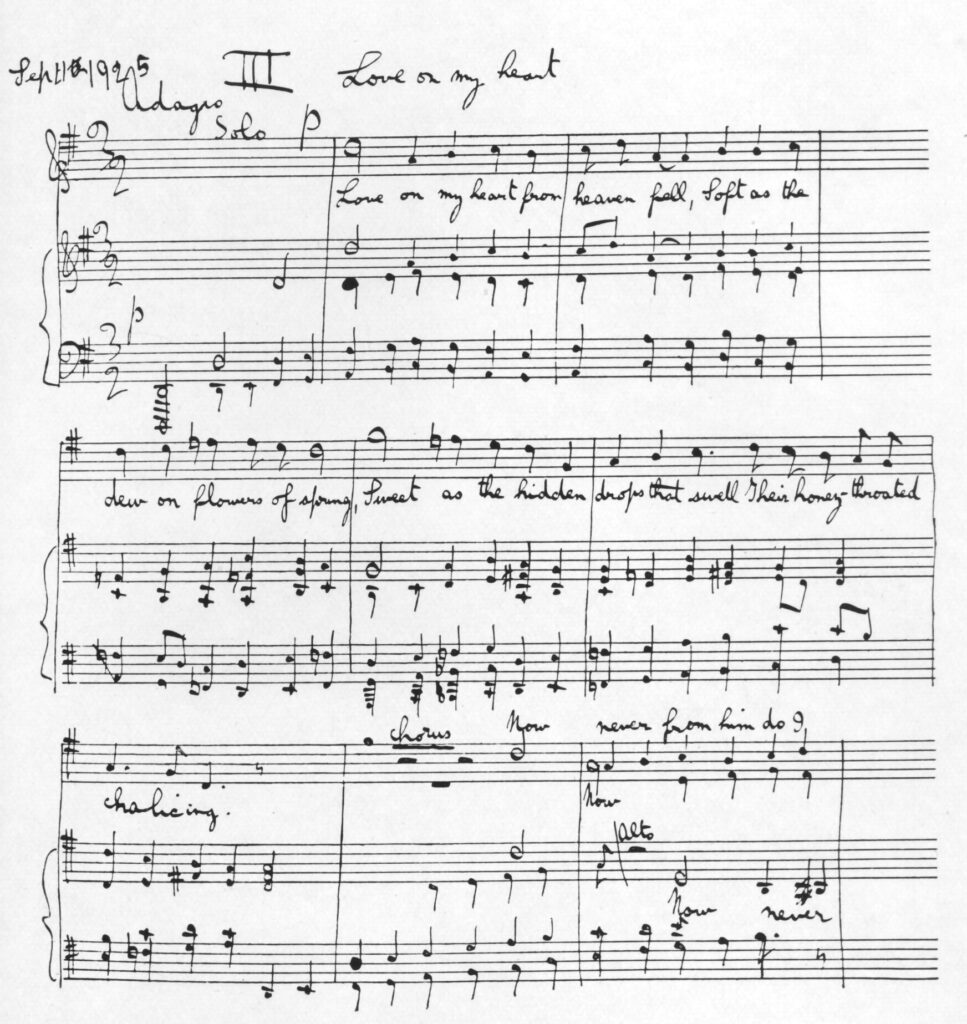

The driving force behind the work was the poetry of John Keats. Holst, a voracious and eclectic reader, did not merely set a single poem to music; rather, he curated a “Keats Symphony,” assembling verses from Endymion, Ode on a Grecian Urn, and various other fragments to construct a cohesive four-movement symphonic architecture.

- Prelude & First Movement: A setting of the “Invocation to Pan” and a Bacchanal.

- Slow Movement: A contemplation on the Ode on a Grecian Urn.

- Scherzo: A nimble setting of Fancy and Folly’s Song.

- Finale: A setting of Spirit here that reignest.

Musically, Holst employed a “pliant recitative” style, allowing the natural rhythms of Keats’s speech to dictate the musical meter rather than forcing the words into a rigid structure. As Michael Short notes, the harmonic language is permeated by the interval of the perfect fourth, marking a decisive shift away from traditional thirds-based harmony toward a sound world that is open, austere, and distinctly intellectual.

The symphony premiered at the Leeds Triennial Festival on October 7, 1925, under the baton of Albert Coates, with Dorothy Silk as the soprano soloist. However, the London premiere a few weeks later proved disastrous. The choir was tired, the orchestra under-rehearsed, and the reception was chilling. Audiences expecting the technicolor fireworks of The Planets were baffled by this work of “chilly, classical beauty.” Critics dismissed it as dreary, and even Holst’s closest friend, Ralph Vaughan Williams, confessed to feeling only a “cold admiration” for it.

A Final Redemption

The story of the symphony has a touching coda. In 1934, only months before his death, the BBC broadcast a performance conducted by Adrian Boult. Holst, too ill to attend, listened from his sickbed. Imogen Holst records that her father was thrilled, feeling that his vision had finally been realized by a competent performance. Perhaps most meaningfully, he received a letter from Vaughan Williams shortly after the broadcast, finally offering the validation Holst had sought a decade earlier: “I wholly liked the work for the first time… it’s you, which is all I know & all I need to know.”

Bibliography

- Holst, Imogen. The Music of Gustav Holst and Holst’s Music Reconsidered. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Mitchell, Jon C. A Comprehensive Biography of Composer Gustav Holst with Correspondence and Diary Excerpts. Lewiston, N.Y.: E. Mellen Press, 2001.

- Short, Michael. Gustav Holst: The Man and His Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.